Searching

the Internet is reading

Investigation

of an Unnoticed Aspect of Information Literacy

By Jeppe Bundsgaard,

The Danish University of Education

jebu@dpu.dk ·

www.jeppe.bundsgaard.net

Paper

presented at The European Conference on

Educational Research Geneva 2006.

Network 3. Session

6: 2006-09-14 10:30-12:00, Room UNI PIGNON S01.

1.

Information

literacy

The

American Library Association provided a capstone for information-literacy

efforts (Seamans 2001: 14) when issuing a report on information literacy (ALA

1989, supplemented by a progress report 1998), defining information literacy in

the widely cited words: To be information literate, a person must be able to

recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate,

and use effectively the needed information (ALA 1989: §3). A number of other

definitions and descriptions of information literacy has been developed (cf. Eisenberg

et. al. 2004), among them the widespread Big6 Skills (for example Eisenberg et.

al. 2000) consisting of 6 steps in a process from task definition to

evaluation. All of the definitions have a step or a category focused on to

locate (ALA 1989: §3) or on Location & Access (Eisenberg et. al. 2000). In this paper I will present a

closer description of skills necessary to master a very common and increasingly

important key type of location of information, i.e. full text search on the

internet.

In USA

information literacy have been standardized in relation to K12 (American

Association of School Libraries and Association for Educational Communications

and Technology 1998) as well as aimed at college and university students (The

Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) 2000). ACRL formulates

their standards thus:

The information literate student determines the

nature and extent of the information needed [

] accesses needed information

effectively and efficiently [

] evaluates information and its sources

critically and incorporates selected information into his or her knowledge base

and value system [

] individually or as a member of a group, uses information

effectively to accomplish a specific purpose [

] understands many of the

economic, legal, and social issues surrounding the use of information and

accesses and uses information ethically and legally (ACRL 2000).

The

standard concerning accesses needed information effectively and efficiently

(Standard 2) among other things includes:

2. The information literate student constructs

and implements effectively-designed search strategies.

Outcomes Include:

a.

Develops a research plan

appropriate to the investigative method

b.

Identifies keywords, synonyms

and related terms for the information needed

c.

Selects controlled vocabulary

specific to the discipline or information retrieval source

d.

Constructs a search strategy

using appropriate commands for the information retrieval system selected (e.g.,

Boolean operators, truncation, and proximity for search engines; internal

organizers such as indexes for books)

e.

Implements the search strategy

in various information retrieval systems using different user interfaces and

search engines, with different command languages, protocols, and search

parameters

f.

Implements the search using

investigative protocols appropriate to the discipline (ACRL 2000).

Standards

like this lay the weight on the library kind of information literacy which

surely is very important, and makes it natural for the librarians to be the key

educators of information literacy, as is often the case (Joint Information

Systems Committee 2002). Today there is a large body of course and curriculum

development in relation to helping students developing information literacy

(Salony 1995, Seamans 2001, Mercado 1999, Eisenberg et. al. 2004, Eisenberg et.

al. 2000). These courses focus among other things on locating the

information, choosing the right database, developing search strings, knowing

how to use Boolean operators, and other techniques etc. But

there is an aspect of this location of the information that seems to be left

unnoticed, namely the steps from developing search words to having found the

information searched for.

Now, what does

it (also) mean to construct and implement effectively-designed search

strategies on the Internet? I will argue that part of information literacy is connected with reading

skills and therefore should be a part of the curriculum of mother tongue

education.

2.

Searching

is reading

When searching

the Internet it is important to be aware of the two fundamentally different

searching methods: The one is register

search (for instance with Yahoo) or surfers

search (on links pages) where one in search for concrete information follow

links describing in some way more or less abstract categories. This kind of

search also demands interesting kinds of reading strategies, but I will not deal

further with this issue in this paper. The other method I call full text search where one in principle

search in the full texts of the entire Internet. The search machine (for

instance Google) keeps a copy of billions of Internet pages in its own memory,

and an inverted index of all words found in these pages.

1.1.

Reading a potential text

A full text

search returns pages in which all (or some, depending on the search machine) of

the words are found. This imply that developing search words is not the same in

full text search as in register

search; in the second case one has to find more abstract words describing

the concrete topic or subject searched for. In the full text search one has to

think of words that are found on a page discussing the subject and not on to

many other pages. Often words designating the abstract topic or subject of the

text is not present in texts discussing the topic or subject so when doing full

text search, one has to not use such topic words. In other

words, to have success one shall imagine,

or read, a potential text. A pretty strange reading strategy.

When the

potential text is read some words is chosen from it. These words are typed in

the search field and the search machine returns hits on a links page.

1.2.

Reading a fragment

A links page consists of a number of hits each composed of a title (which

is active as link), an URL (Internet-address), diverse information on the

document, and a few fragments of the text from the document.

Figure 1. A Google hit.

The key part of full

text searching is to be able to read the title and the fragments. A fragment

is a short machine computed extract of the text. Each fragment contains one or

more of the search words (indicated by bold typeface); and the fragments are

separated by three bold dots (

). Thus

when reading a hit one put into practice a number of reading strategies; the

most important of which is fragment

reading. Fragment reading is successful when the reader is able to work out

an adequate imagination of the contents of a page on the basis of the page

title, and a few more or less random fragments.

This kind of reading requires that the reader use his textual, intertextual,

and contextual knowledge, including his

·

Intertextual genre knowledge; for

example the reader could ask: Does this seem to be

o

a front page that mentions the

search words, but doesnt deal with it,

o

a page that deals with another

aspect of the subject than searched for,

o

a news group page, or a news

article, that is out of date or only includes the question, and not the answer

o

a commercial page, for example

a book store selling books with the search words in the title,

o

a page referring to another

page that includes the search words,

o

a personal home page under

construction, etc.

·

Textual knowledge of difficulty and style; for example the reader could ask: Does this seem to be

o

too informal language to handle

the subject seriously, or too formal to be understandable,

o

too comprised to get sufficiently

in-depth with the subject, or too narrative to be exact,

o

too personal to be relevant,

etc.,

·

Contextual knowledge of the producer and production realities; for example the reader could ask:

o

what seems to be the qualifications

of the producer,

o

which kind of home page

(university, news group, personal home page) is this,

o

what might be the producers

interests and goal, etc.

That is to

say that the reader has to infer lots of information from very short bits of text.

These suggestions about adequate reading skills indicate that it is a very

complex practice to read fragments, and the reason why I wouldnt recommend

teaching Internet full text search before the children has developed very efficient

reading skills, for instance in fifth or sixth grade.

1.3.

Survey reading of fragments

But even

before we close read the fragments, we survey read them to get an impression of

the general success of the search. Survey reading of fragments of course is

very different from survey reading of coherent texts, because when survey

reading fragments one has to enact the reading strategy of fragment reading,

and in the same time screen out all the less important details.

If the survey

reading indicates that the search words hasnt resulted in pages that gives the

answer to the question, one has to return to the first phase, and try to choose

other search words or supplement the old with new ones, and possibly by

excluding words (with a minus-sign or the Boolean operator NOT) which appear

frequently in the fragments, and which is not likely to be on a page that has

the answer to the question. These choices are based on additional reading of

the potential text, and by investigating what is causing that the texts on the

links page is not considered relevant answers. In other words: It is as

important to be able to decide what to not

read as it is to be able to read.

1.4.

Survey

reading

When finally a number of texts are chosen for further inspection, and when

a link is followed to a text that might have the answer, the first thing to do

is to survey read this text. Even

though the text to survey read is a coherent text, the survey reading often

does not resemble survey reading of encyclopaedia texts or news paper texts.

Survey reading of Internet texts is far more concerned with reading of

contextual and textual clues in the text and with reading of the layout,

structure, and production details of the text.

On the computer screen a text is not just written, but also always an image

(Kress 2003: 65ff.), and it consists of a number of modes (writing, icons,

images, colours, and even spoken words, music, and sound) that all contribute

to create the meaning of the multimodal text.

That is, the text is to be read as a multimodal text: One looks at the

overall impression based on layout: Does this page seem to be professionally

produced, or by some one that appears as reliable of other reasons, does it

seem to be on the level of seriousness I am after; one looks for structure and thoroughness:

Does this page seem to be of the kind that would deal with the subject I am

searching information on (or is it for example a travel agency)? Etc.

When this first survey reading is done, one has to find the part of the

text that deals with the subject searched for. Sometimes it is only a rather

small part that does that, and then one has to find out where that is. This can

be done by searching for the key words with the browser functionality to

internal full text search (Find on this page) or with other tools (for

instance the Google toolbar).

And finally one can continue with a more common survey reading to get a

grip of the texts communication on the subject.

1.5.

Close

reading

It is my experience as well as the experience of many school teachers I

have talked with, that students often are of the opinion that when they have

found a text that discusses the subject, they are through. This understanding

might have a number of explanations, ranging from their lack of interest in the

subject to the experience of information overload, and that having the

information as text is enough, while actual understanding of it is unattainable

or undesirable.

None the less the close reading part of a search is in the end the Alpha

and Omega. Close reading is of course done to understand the information, but

it is also done to have a base for critical reading of the information: Among

other things with the purpose to take a position on the correctness and value

of the information, as well as on the interests and goals of the producer.

Close reading an Internet text is in form very comparable to close reading a

text in a book, but there is a difference that makes a difference, which is

that we cant be sure that texts on the Internet has been through the editorial

process that most books and other texts printed on paper has. One of the most decisive

differences between pre-Internet school and post-Internet school is the amount

of texts sanctioned by gate keepers like editors, librarians, and teachers. In

pre-Internet time it was close to every text that was sanctioned by at least

one gate-keeper, today there are a constantly growing number of texts that

nobody sanctions before the student reads it. Thus in principle, the student

has to develop the competence to be his own gate keeper. This is not only a

necessity in school, but also a very important competence outside of school

in this way the non-gate kept Internet is a blessing in disguise.

1.6.

Critical

reading

I have argued that critical reading is a necessity. But it is also very

difficult. It involves a number of the before-mentioned reading strategies, but

in a different mode and mood. Critical reading is reading a text to get a grip

of the texts and contexts behind the text. Questions like: Who is the producer

of this text, what are his interests, goals and qualifications. To read

information on the producers qualification, interests and goal, one can "read" the layout, the

style and language of the text using survey and close reading strategies,

clicking through to pages telling about the producer, and maybe even search the

Internet for information on the producer. And one can examine choice of words,

metaphors, modalities, and deixis, and analyse arguments, references etc., i.e.

perform discourse analysis.

1.7.

An

overview

Thus these deliberations

show that searching the Internet requires a number of reading strategies. These

are summed up in the following figure:

To search the Internet

with full text search machines, one has to master these reading strategies:

·

Reading a potential text (imagining a text, reading it in

search of adequate search words)

·

Reading fragments of texts (imagining a text by reading

machine-produced fragments of it (on the hits page))

·

Survey reading of fragments (to decide if the search words

resulted in adequate hits)

·

Survey reading the texts selected for closer study

(to see if they are as expected (contents, layout, difficulty etc.))

·

Close reading the passages with the searched

information (to decide if it should be selected for use or closer inspection -

often comparing several texts to get different views).

·

Critical reading of the qualifications, interests and

goals of the producer of the text(s) ("reading" the layout, the style

and language, "reading the interests of the producer (examining choice of

words, arguments, references etc.), and reading the qualifications by

examining the web page and the Internet for information on the producer).

Figure 2. Reading strategies when full text

searching on the Internet

3.

An

example

These reading

strategies are by no means trivial to master. In the following extract from a

dialogue between three eight graders (about 14 years old), I will point to some

of the places where problems may arise.

The

dialogue was centred around a number of tasks on a webpage. The main theme of

the tasks was the movie and book trilogy Lord

of the Rings. The students were among other things asked to find out the

meaning of the word amon which is a

word in the Sindarin-language which

is invented by Tolkien. I were sitting next to the three students, helping out,

asking and answering questions etc., and videotaping the students and their

computer screen.

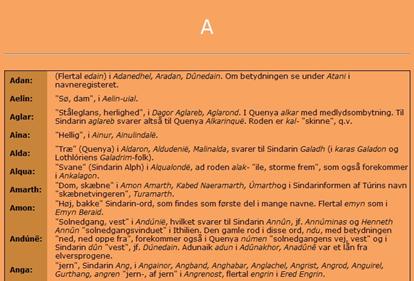

Figure 3. Task: Find the meaning of the word Amon

The exercise

could be solved quite easily for example with these search words: amon sindarin "lord of the rings"

dictionary. Michael is handling the mouse and keyboard. Eve is actively

participating, Susan mostly sitting in the background.

The

students click into the search assignment, and read in silence, however one of

the girls is heard saying Sindarin

with low voice. They choose Google as search machine.

1 Michael: Because

(writes)

. You search on...

2 Eve: I

think you should write

(points to the

screen).

3 Michael: Lord of the Rings, or?

4 Susan & Eve: Yes (Michael writes the

search word in the search field, clicks the search button, and Google opens

with the result).

In this short dialogue fragment the students choose as their search

words Lord of the Rings (in Danish: Ringenes Herre) which will yield nearly

a million hits in Danish. It seems likely that the students either think of the

search as a thematic search or that they correctly imagine that the text they

are searching for contains the words Lord

of the Rings. The problem in this case is that a lot of other texts contain

the same words and that it is not very likely that the pages with the highest

rank are explaining the meaning of the word amon.

Therefore the students should have spent more time reading the potential text

to supplement the search with more words from this potential text.

They arrive at a links page similar to this one:

Figure 4. Google Search: Ringenes Herre

5 Susan: How

is it you can se

(Points far away from

the screen)

6 Michael: Wau!

[inaudible]

facts.

7 Eva: Teaching

materials, if you try that (points to one

of the top links).

8 Michael: Right,

lets try that.

Figure 5. Teaching material

(www.sf-film.dk/undervisning/)

9 Eve: Okay,

that wasnt just

(after having looked on the page for about 2

seconds).

10 Michael: No.

11 Eve: It

might be there though (while Michael is

clicking back to the search result).

12 Susan: Then

youll have to find somewhere where you can search [implied: on the site].

13 Eve: Mnn.

The students have arrived at the links page and start reading. Michael

notices a word in the first hit: Facts

(fakta), which implies that he is in fact reading the

fragments. By mentioning the word facts,

Michael shows that he attaches importance to it. I interpret it thus that he

thinks: I am searching for facts, this page has facts, let me try that. I

identify this as a rather poor imagination of the text, showing that he is all

too optimistic in his reading, and in his expectation of the producer having

the same interests and goals as he has; an optimism that results in a superficial

reading of the fragments.

It is not possible to see clearly from the dialogue, whether the

students survey read the fragments at this stage, but it doesnt seem so.

Anyway, the students decide to click on the second link (which is part of the

same website as the top link, shown by indention of the text): Teaching material, and they arrive at a

screen with three movie posters, one for each movie in the trilogy. Eve is very

fast in rejecting the page, showing her survey reading skills (l. 9). Michael

agrees (l. 10), but then Eve is having second thoughts, which Susan express as

the possibility to search on the site which apparently is centred around the

movies, and therefore could be expected to include information on the meaning

of the word amon. Had they done that,

they would have stopped the Internet full text search and started on a surfers

search (maybe supplemented with local full text search). But Michael decides to

return to the Google links page.

14 Michael: Amon

(says the word as to him self) Amon (apparently looks for the word among the links).

15 Eve: No,

thats

[mumbles].

(Michael moves the pointer downwards, Eve

presses the arrow-down key, so the page rolls down to the last results).

16 Michael: Facts

17 Susan: [inaudible]

(points to a link on the page)

18 Michael: (After having looked at the links page for

about 30 seconds) The adventure of the ring.

19 Eve: Just

try it, we might

(Michael clicks on a

new link. Moves the pointer around the page, about 4 seconds. )

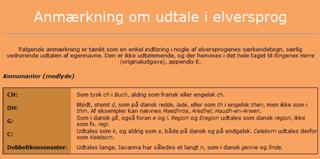

Figure 6. Page about LOR at the movie site Scope

(www.scope.dk/film.php?id=1503)

20 Eve: Okay

[inaudible] (seemingly impressed by the

page).

21 Susan: (Points to the search field in the top of the

left menu under which it says Advanced search). Try to click below the

search field.

22 Eve: Its

ehh

(Susan turns towards Eve, but she

doesnt finish her sentence).

23 Michael: (Looks where Susan is pointing, but soon

moves on, rolls down with the mouse and thereby refuses Susans suggestion).

24 Eve: Try

to go back instead [inaudible]

25 Michael: (Clicks the browsers back button, looks at

the page before it shifts, and discover a link to facts at the middle on the page, points with the

mouse). Hey! There were facts. What do you think it was?

26 Eve: Go

forward (points to the forward button.

Michael clicks forward and then clicks on the facts link. But it is not a link

the page they are viewing, is the facts page).

27 Michael: What

do you think we shall do here?

28 Eve: It

doesnt really say anything.

Michael starts out by looking for the word amon which is not among the search

words, and therefore very unlikely to find on the links page. But it shows that

Michael is not unfamiliar with the thought that the word shall appear on the

page. They read on the page for a long period of time, possibly both fragment

reading and survey fragment reading. But they dont use their falling confidence

in the search to revise their search words. Michael ends up suggesting one of

the other links on the page, which has the words Lord of the Rings in the title. Eve is impressed by this page and

takes some time looking and survey reading it. Susan proposes the advanced search,

but doesnt get support for the suggestion. Eves reading leads to that she

judges the page futile (l. 24). Just when Michael has clicked back to the links

page, he finds the word Facts again

(l. 25) clearly indicating that he imagines his search to be fact finding,

and he imagines the producer of the page to have the same interest in the word amon as he has, therefore having it as a

top priority to tell about the meaning of amon.

As a consequence of this interpretation I will characterize Michaels imagination

of the communication situation as of type 1 (cf. Bundsgaard 2005b, see Figure 7), that is to say an imagination of the producer

having the same object in focus as the consumer/searcher, as we also saw

earlier.

|

Type I.S2

imagines a diffuse producer (often referred to as them, even if S1 is

only one person). S2 expects O for S1 and the text to

be the same as S2 searches information of. The text is attributed authoritative status

it is written there,

so it must be true.

|

|

Type II.S2 tries

to imagine what the project of S1 is and through that considers

where in the hypertext the information is to be found.

|

|

Type III.As Type II, but

including a critical assessment of S1's qualifications and interests based on

analysis of the content and appearance of the page.

|

|

Type IV.As Type III, but

furthermore tries to find out what project, qualifications and interests S1

has by searching contextual information on S1 (e.g. by going to

the first page in the hypertext hierarchy).

|

Figure 7. Typology of imagined communication

situations (Bundsgaard 2005b: 209).

This imagination clearly causes the group

difficulties, because they dont expel the pages with a general approach to Lord of the Rings quick enough.

29 Michael: (Clicks back again. Looks thoughtful).

Maybe it said something about being from Sindarin or something?

30 Eve: I

dont think

31 Michael: Look

(Clicks to the exercise from the taskbar).

It is a (Eve joins in) Sindarin word.

Sindarin. Shall we try to write that?

32 Susan: Lets

do that.

33 Michael: (Places the pointer in the search field)

Shall we write it down here?

Or: Lord of the rings? (Gesticulates inquiringly).

34 Eve: Yes

(Michael writes Lord of the Rings).

35 Michael: And

then in brackets? Or what?

36 Eve: No,

just write it

37 Michael: Sindarin.

38 Eve: Yes.

39-42 (Michael clicks the wrong place. Eve helps

him back on track).

43 Michael: (They look at the links page, Michael and Eve

both says something in low voice, and points to the same link on the middle of

the page). Shall we try that?

44 Eve: Yes (Michael clicks and they arrives at Chaias home page).

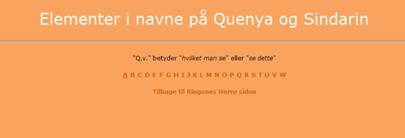

Figure 8. Chaias home page on pronunciation of

Elvish

45 Michael: Pronunciation of Elvish.

46 Eva: Yes, that one (They look at the page for about 25 seconds;

Michael moves the pointer down the page). No, I dont think it is this one.

There was another one which was good.

47 Michael: No, eh [inaudible] (Clicks the browsers back button).

48 Susan: There was another where it said

Sindarin.

49 Eve: Was there? (Points to a link, and Michael clicks).

Figure 9. Chaias home page: Elements of

names in Quenya

and Sindarin

50 Michael: There is A, you see (Clicks on A).

Figure 10. Chaias home page: The letter A.

51 Eve: A (They read for a while)

52 Eve

and

Michael: Amon. Hill. A Sindarin word which is

found

53 Michael:

as the first part of many

nouns. Plural

But it is Hill

54 Eve: Yes.

Michael

remembers (l. 29) that amon was a Sindarin-word, and suggests that they

write that. At this point he returns to re-read the potential text, this time a

little more detailed. But he and the others still dont use the word amon in their search. Arriving at the

links page, it doesnt take long for them to find a home page by a young Danish

girl on Lord of the Rings. The first

page they click into contains the word Sindarin,

but not Amon. They take some time

surveying it, and then reject it. The next link the students choose is from the

same home page (l. 48-49), but they dont realize that. At this point they

leave the full text search and enters surfers search by surfing from the page

that contains the words they have searched for (Lord of the Rings and Sindarin).

But they are lucky to arrive at a page containing the explanation of the word amon.

The

students seem to have a good reading competence, but they arent aware of the

different ways to read the pages in an Internet full text search. This is

reflected in their search, and to a certain degree makes it haphazard that they

end up with the right answer.

The

students particular challenges are found in imagining a potential text, in

reading fragments and in survey reading fragments. But they clearly also

doesnt notice which home pages they visit and what the qualifications,

interests and goals are of the producer.

4.

Conclusions

and invitations

In this

paper I have pointed out that there seems to be a lacking attention to the part

of information literacy that has to do with coming from developing search words

to having found the page. I propose to view this as a question of reading, and

I introduce a categorization in 5 types of reading strategy:

- Reading a potential text,

- Fragment reading

- Survey fragment reading

- Survey reading

- Close reading

And as a

combination of the other five types:

- Critical reading.

I have

described in this and several other contexts how these reading strategies are

enacted by students and how they are not enacted, and I have proposed some approaches

to help students develop these reading strategies (cf. Bundsgaard 2005a:

5.3.1.1 & 5.3.3.; Bundsgaard & Kühn forthcoming). But surely there is a

lot of work to be done in this context. I will emphasize the need to know more

about how the everyday search practise is, how it can be improved by imposing

changes in strategies, how it can be practised and so on. And I will emphasize

the considerable need to understand how skilled searchers and students do

critical reading, and how to improve it.

5.

References

American Association of School Libraries (AASL) and Association for

Educational Communications and Technology (AECT) (1998): Information

Power: Building Partnerships for Learning. Chicago: ALA

The Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) (2000): Information

Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education. Chicago,

Illinois. http://www.ala.org/ala/acrl/acrlstandards/informationliteracycompetency.htm

American Library Association (ALA)

(1989), Presidential Committee on

Information Literacy: Final Report. http://www.ala.org/ala/acrl/acrlpubs/whitepapers/presidential.htm

American Library Association (ALA) (1998), A Progress Report on Information Literacy: An update on the American

Library Association Presidential Committee on Information Literacy: Final

Report. http://www.ala.org/ala/acrl/acrlpubs/whitepapers/presidential.htm

Bundsgaard,

J. & Kühn, K. (forthcoming): Danskfagets

it-didaktik. København: Gyldendal.

Bundsgaard, J. (2005a): Bidrag til

danskfagets it-didaktik. Med særligt henblik på kommunikative kompetencer og på

metodiske forandringer af undervisningen, Ph.d.-dissertation,

Odense: Forlaget ark. http://www.did2.bundsgaard.net

Bundsgaard, J. (2005b). Imagined communication situations In: M.A.

Carlsson, A. Løvland, G. Malmgren: Multimodality:

Text, Culture and Use.

Kristiansand:

Høyskoleforlaget. Norwegian Academic Press, pp. 199-211.

Eisenberg, M. B. et al. (2004): Information Literacy. Essential skills for the information age. 2.

ed.Westport: Libraries Unlimited.

Eisenberg, M. B. & R. E. Berkowitz et al. (2000): The Big6TM in Secondary Schools.

Worthington, Ohio: Linworth Publishing Inc.

Kress, Günther (2003): Literacy in

the New Media Age. London:

Routledge.

Mercado, H. (1999), Library instruction and online database searching,

Reference Services Review, Vol. 27 No. 3, pp. 259-265.

Salony, M.F (1995), "The history of

bibliographic instruction: changing trends from books to the electronic

world", The Reference Librarian, No.51/52, pp.31-51.

Seamans,

N.H. (2001), Information Literacy. A Study of

Freshman Student's Perception, with Recommendations. Ph.D.-dissertation. http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/theses/available/etd-05142001-104550/unrestricted/Seamans.pdf

Joint

Information Systems Committee (2002): The

big blue. Information skills for students.

http://www.library.mmu.ac.uk/bigblue/pdf/finalreportful.pdf